America’s Birth Rate Crisis

Kamala Harris' believes she has the solution

It’s been a while since our last update, and today we’re focusing on a critical yet often overlooked issue: the sharp decline in birth rates across America. Despite its profound implications, this crisis hasn’t received the attention it warrants. What we initially expected to be a routine policy review turned into something far more compelling.

Our Recent exploration of logistics news:

FedEx: Breaking up?: FedEx may be most undervalued before it announces its breakup.

Brown No Longer: UPS's Downfall: How UPS changed from a logistics powerhouse to a struggling giant.

Amazon: Built on Welfare: How Amazon uses tax policies to its advantage.

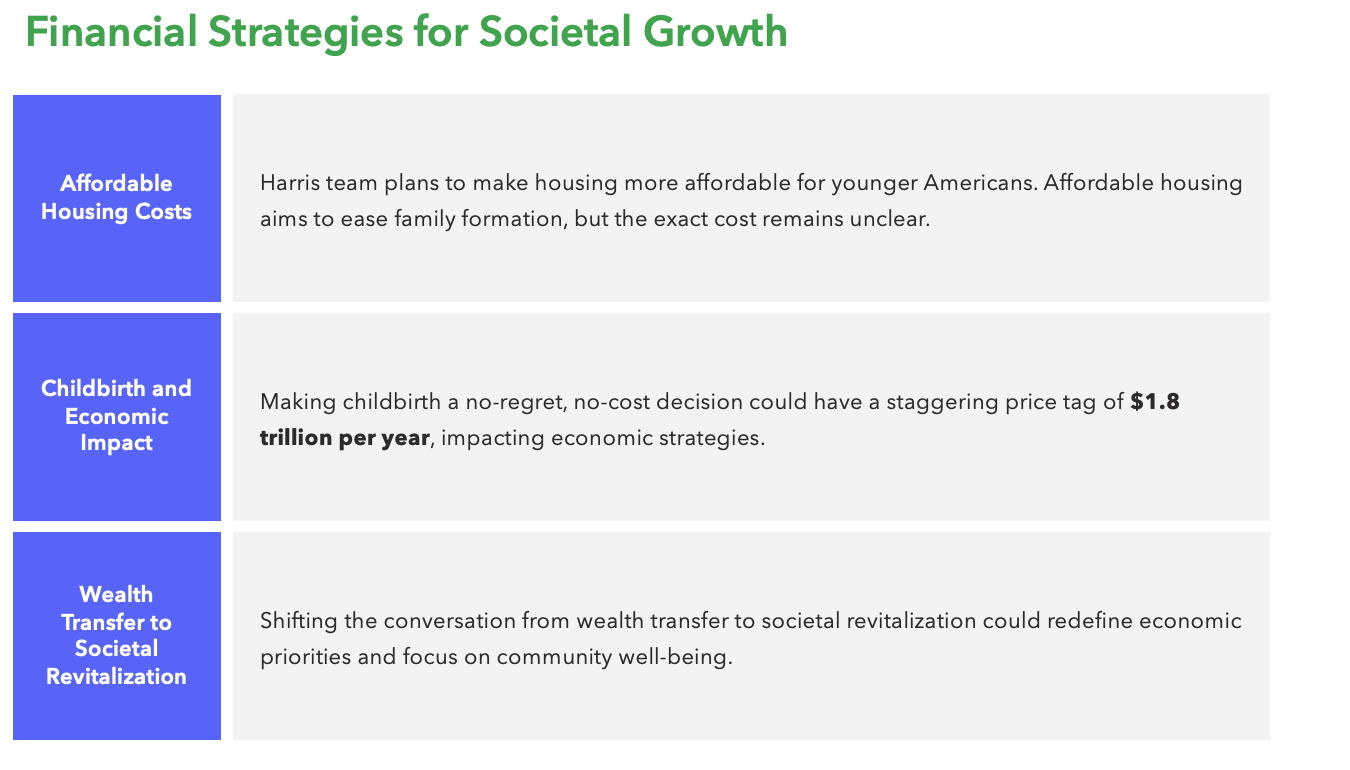

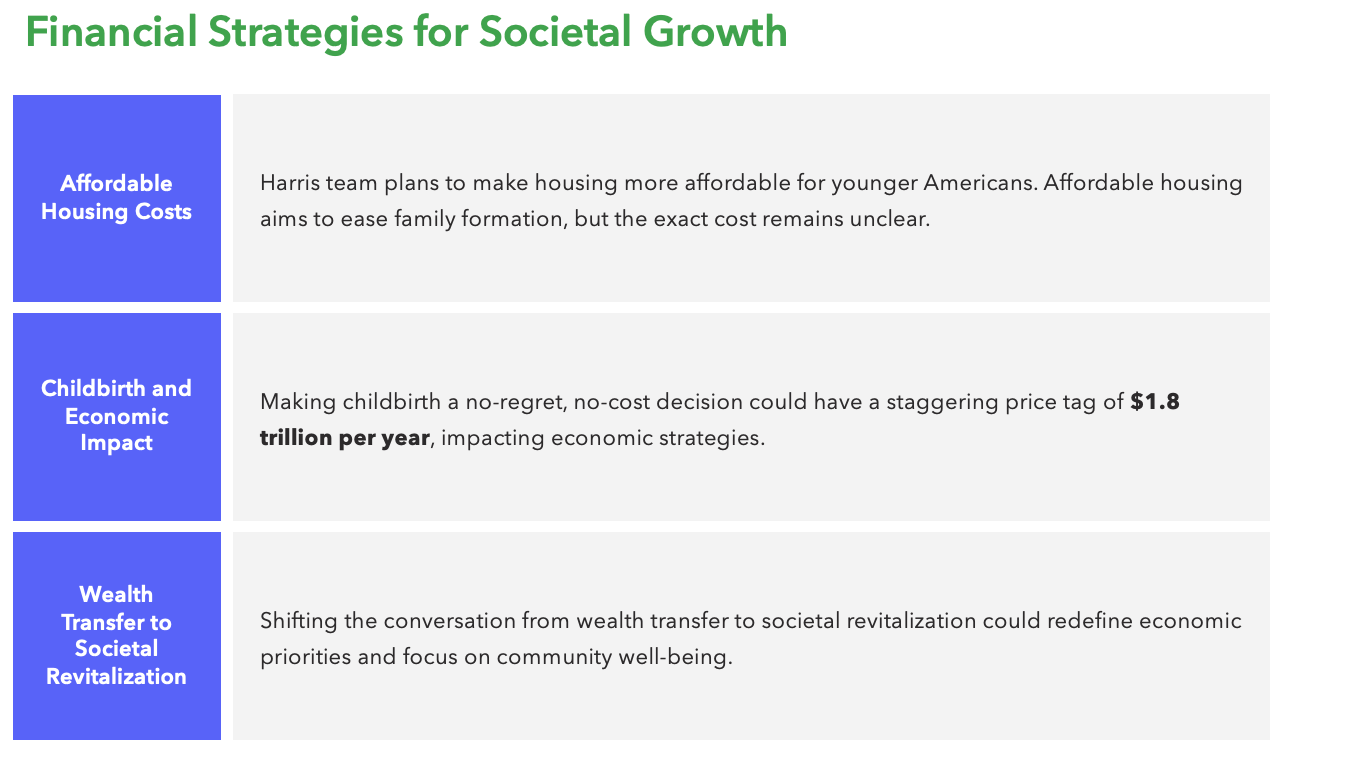

According to a document titled Financial Strategies for Growth, the Harris campaign strategy to tackle the birth-rate crisis rests on three key pillars: making housing more affordable, ensuring childbirth is a no-cost, no-regret decision, and reframing the national conversation from wealth transfer to revitalization. Perhaps the most impactful aspect of the plan is what’s being called “Social Security for Children,” which aims to gradually increase child tax credits to $20,000 in the coming years, fundamentally reshaping what it means to bring a newborn into the world in America.

"We need bold, transformative action to secure our future, and it’s going to take serious money and guts—both of which Kamala Harris has in abundance," said a Harris campaign official."Radical," snapped a Trump aide when asked for his thoughts.

A changing America

America's demographic challenge is hard to miss, yet few seem eager to confront it: the country's birth rate has plummeted.

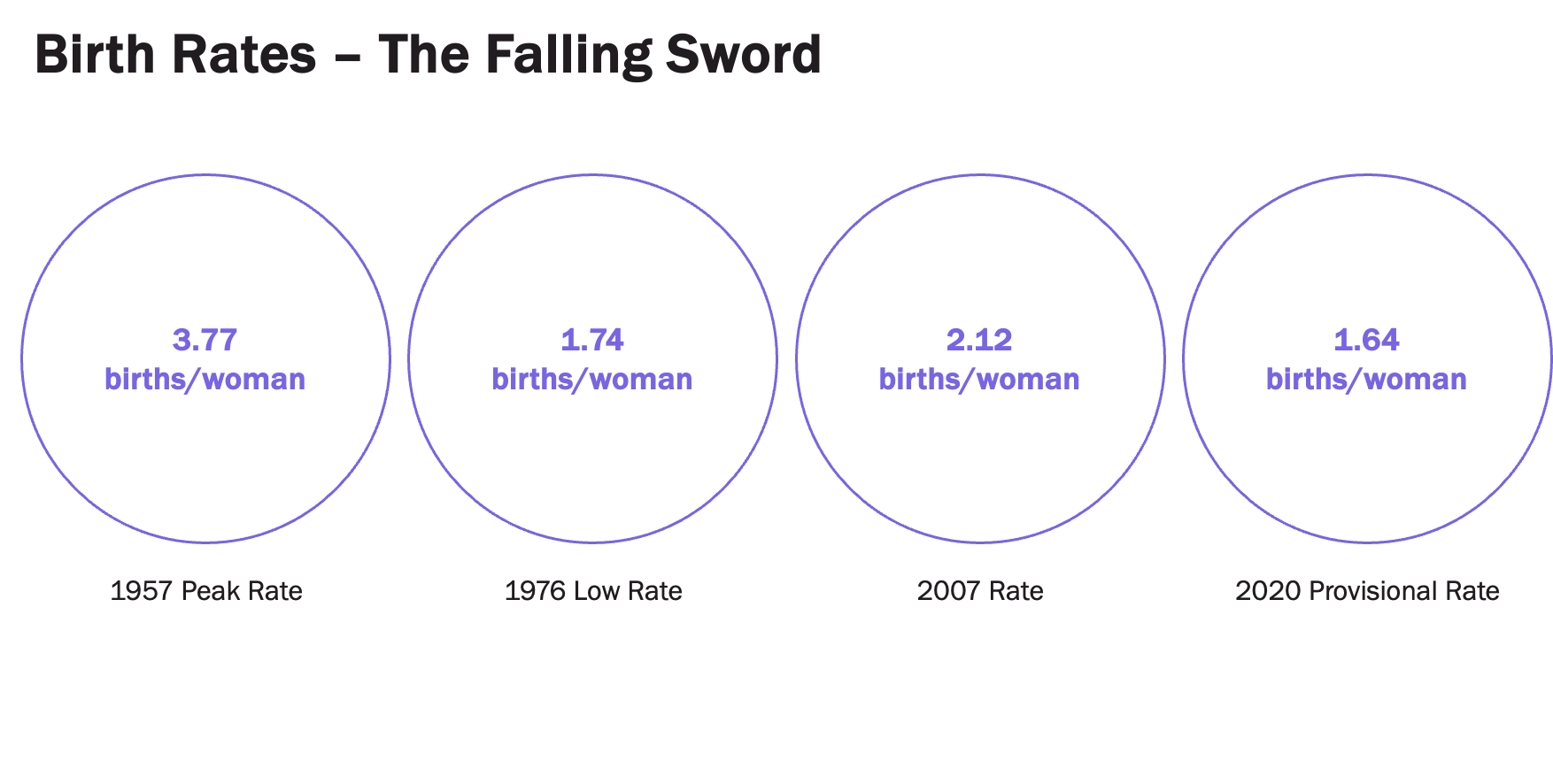

In 1950, life expectancy was just 68 years, and families were raising an average of 3.58 children. Fast forward to today, life expectancy has stretched close to 80, while the fertility rate has collapsed to 1.64—well below the replacement threshold of 2.1.

"We reap what we invest in," notes a leading economist in demographic trends. "Support the elderly, and you get an aging society. Support the young, and you foster growth."

This demographic shift presents a stark challenge. It’s not about choosing between the future and the present—America can, and must, balance both. As healthcare costs balloon, now accounting for 20% of GDP compared to just 5% in 1960, spending on education and housing has surprisingly remained roughly the same proportionally as they were 50 years ago. The country's resources have tipped heavily towards the old and the trend continues.

A senior Harris campaign advisor captures the urgency: “A child is a dream. What we aim to do is make that dream economically neutral, so families can rebuild the American dream."

In contrast, a Trump aide takes a different tack: "Family values don’t mean charity. Tax deductions are nothing more than a socialist wealth transfer.”

For this feature, we sat down with senior advisors on each side to understand their visions. Both camps have proposed distinct solutions to spur growth: free IVF from Trump, and a $6,000-per-year child credit from Kamala Harris. But the divergence runs deeper. While Trump’s team frames the crisis as cultural, Harris's strategy places the burden squarely on economics. And they have ambitions beyond just tax relief.

“By the end of our first term, we aim to be on our way to establishing Social Security for Children,” confided a Harris aide speaking on condition of anonymity.This plan if it is fully realized will cost $1.8 Trillion a year, roughly the same as what the government spend sof social security today. With a declining population, we believe this is the right plan.

Aging or the New Feudalism?

The demographic transformation America faces on surface seems to be a homogenous trend. We just stopped having children. But look a little deeper, and cracks emerge.

“A society in which wealthy age, there is less transfer and build up of wealth. Ultimately, such societies become feudal, as more of the energy is spent in protecting capital than building capital,” noted an economist at Harvard.

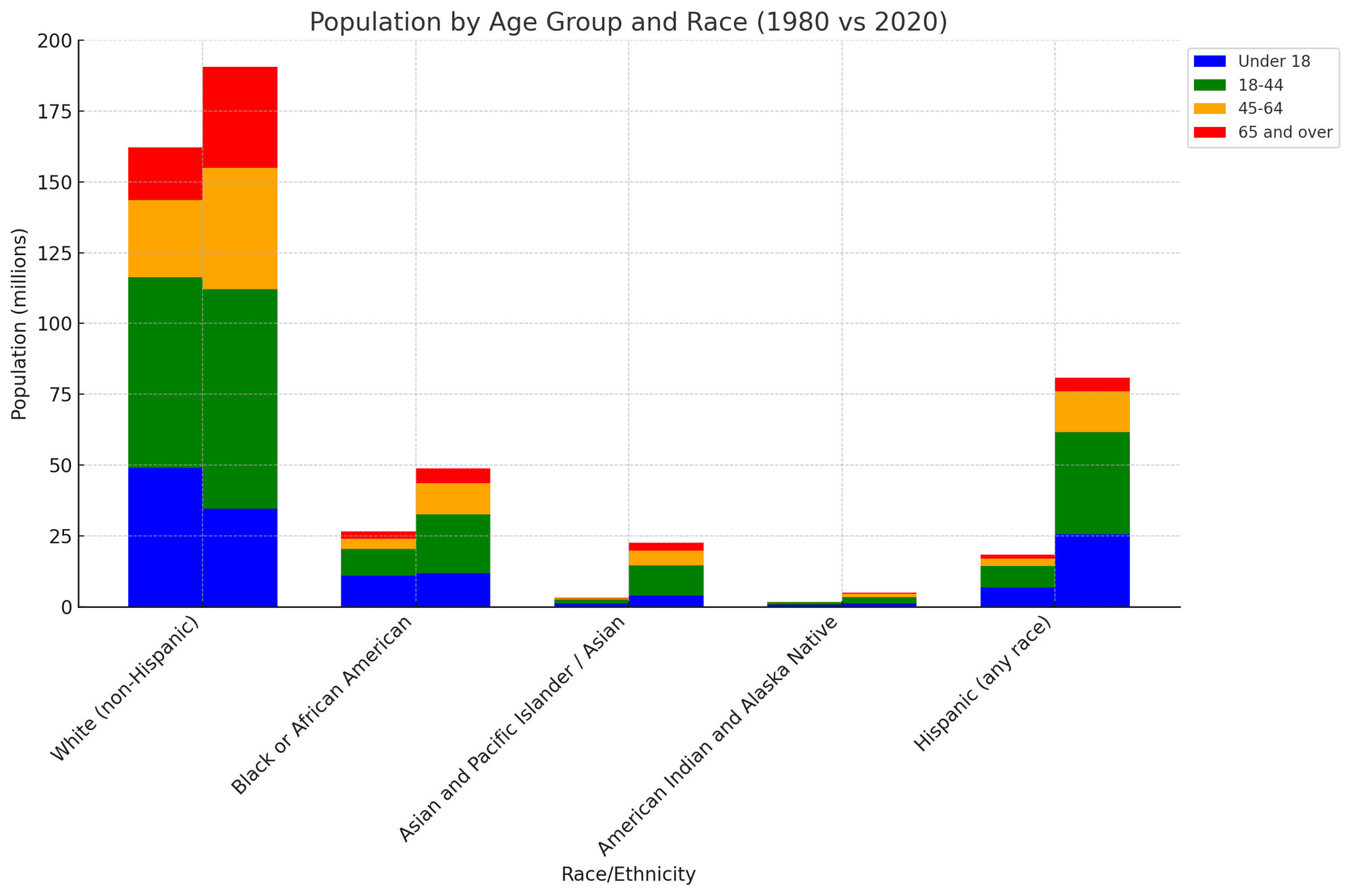

“White Americans, currently control 85% of the nation's wealth. This is roughly the same they did in 50 years back when Whites were 80% of the population. Studies at the turn of the century were projecting this proportion to start to decline, but remarkably, in last 10 years, it has only ticked up slightly,” commented a noted economist at Yale.

"We think of declining child birth in terms of a combined population - but when you look deeper, it’s clear that White women just stopped having children."

“One problem with a capitalist society is it doesn’t have a great mechanism to rearrange assets,” remarked an economist specializing in inequality. “Once you own an asset, you own an asset and it continues to be passed from one generation to the next. Unlike the past, we don’t have the unexplored west where new generational wealth could be built.”

"Generational wealth transfer is entrenched," she continued. "Even as the white population shrinks, their grip on the nation’s assets remains firm. The economic power they wield isn’t easily redistributed."The U.S. Census Bureau projects that while whites will become a minority, they are expected to continue holding the vast majority of wealth. Meanwhile, Hispanic, Black, and Asian populations—who are growing in number—are unlikely to see a proportional increase in their economic influence. "This creates a growing divide," said a sociologist studying systemic inequality. "The question is no longer whether wealth is concentrated, but whether we're sliding into a kind of modern feudalism where a shrinking segment of society controls the levers of power.

As wealth becomes more concentrated among an aging white population, younger and more diverse generations face financial stagnation. "The reality is harsh," noted a policy expert. "Wealth isn't simply a matter of race, but without significant shifts, the gap between the demographics controlling the nation's assets and those growing in size will continue to widen."

This is the backdrop in which Harris team is proposing the most daring agenda:“Unless we start to make tangible changes today, we will see Blacks, Hispanic, and Asians becoming economically and materially marginalized—or worse, see a revolution,” noted a Harris aide. She added, “Today we can still make changes, but the window is closing on us fast."

Birth Rates: A History Lesson

The marginal value of having additional children has been in steady decline for over a century. As industrialization took hold in the U.S., the economic necessity of large families diminished. No longer tied to the land, where more hands meant more productivity, Americans began to see smaller families as not just a preference but a rational economic choice.

“Industrialization shifted the calculus,” observed a sociologist at Princeton. “As jobs moved from farms to factories, survival no longer hinged on the size of the family. Fewer children became the norm, and eventually, the need for large families all but disappeared.”

By the mid-20th century, the U.S. had transitioned to a service-based economy, relying on surplus production and outsourcing manufacturing jobs to countries like China and Vietnam. While economically efficient, this shift metaphorically outsourced the “production” of people as well. The family unit, once central to American economic stability, began to shrink.

Yet, it wasn’t until the until the advent of the birth control pill in the 1960s that this transformation truly accelerated. The pill revolutionized family planning, giving women unprecedented control over their reproductive lives. "It decoupled sex from procreation, allowing women to focus on higher education and careers," remarked a gender studies expert from Columbia University. The impact on birth rates was swift: between 1960 and 1975, fertility rates dropped sharply from 3.65 to 1.77 children per woman.

A demographic researcher adds, "The pill didn't just empower individual choices, it reshaped societal norms. It transformed the role of women in the economy and led to a sharp decline in birth rates."

Economic factors also played a critical role. The 1970s were marred by stagflation and oil crises, fostering financial uncertainty that delayed family planning for many. "When the economy is unstable, people tend to delay major life decisions, like having children," said an economist at the Brookings Institution.

A senior advisor from Harris’s team concurred, "The pill was revolutionary, but the economic landscape was just as important. I couldn’t afford a child at 21, and today, many young women face the same economic barriers. We believe the only way forward is to make having children economically viable."

Another Mini-boom?

Then just as everyone had seemingly given up and decided aging is here for good something unexpected happened.

Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion across the U.S. Many predicted birth rates to fall under 1.5 and they briefly did - initially, birth rates fell, dropping from 15.6 births per 1,000 people to 14.8 by 1976. But by the early 1980s, the decline reversed. Birth rates started to rise again, climbing to around two children per woman by the mid-1990s.

Several factors played into this mini baby boom. The so-called "echo boom" of the Baby Boomers—children of the post-war generation—was one driver. At the same time, immigration surged, and immigrant families traditionally had more children, helping to prop up the fertility rate.

"Immigration masked the underlying decline in native-born fertility rates," observed a demographer from the Migration Policy Institute. "While the birth rates of White Americans continued to fall, the influx of immigrant families with larger households gave the illusion of stability."

Yet the cultural and economic landscape was already shifting. A large portion of the country was slow to recognize this reality, assuming that birth rate declines were primarily a European problem. “People underestimated how swiftly the U.S. was following suit,” noted a sociologist at Columbia University. By the late 1970s, White women were no longer having children at rates necessary to sustain population growth.The momentary uptick in birth rates during the 1980s and 1990s also came at a time of relative economic stability, with many families feeling more confident about starting or expanding households. But this resurgence proved to be fleeting.

As one Harris campaign advisor succinctly put it: “The warning signs were there. Economic uncertainty continued to weigh on families even during periods of growth. Without bold action that put women and children at the center, these fluctuations only delayed the inevitable.”

The Second Collapse: Economic Realities and the 21st Century

By inevitable, she was referring to the Great Recession and sudden breakdown in the pact poorer and younger Americans had with America to be able to build and prosper, no matter what you started with.

As George W. Bush entered the White House, the U.S. was thrust into a series of crises that would define the decade: prolonged wars in the Middle East, a housing boom that primarily benefited the wealthy, and an economic recession unseen by many in their lifetimes. The collapse of birth rates during this period was unmistakable.

"If there were ever a doubt that declining birth rates were driven by economics, the 2000s dispelled it completely," noted a labor economist from Yale. As economic pressures mounted, so did the decision to delay or forgo having children. Even as housing prices soared, wage stagnation meant that young families were increasingly priced out of the very neighborhoods they once saw as part of the American dream.

By 2008, as the financial crisis set in, the U.S. experienced an unprecedented trend: reverse immigration. For the first time, many immigrants who had arrived seeking better opportunities began leaving the country in search of stability elsewhere. "The economic winds blew harshly, and those who could no longer afford to live here—whether they were native-born or immigrants—left," said a policy expert on immigration trends.

At the same time, an aging population meant that more women were exiting their child-bearing years without having the number of children they might have envisioned. By 2020, the U.S. fertility rate had fallen to a historic low of 1.64 births per woman. Factors contributing to this collapse included the rising age of first-time mothers, an increased participation of women in higher education and the workforce, and crushing student debt burdens.“Today's young adults are grappling with economic pressures that previous generations never faced,” remarked an economist from Harvard. "The cost of education, housing, and healthcare has made starting a family a daunting financial prospect."

Cultural shifts have further reshaped societal norms. Delayed marriage, increased acceptance of child-free lifestyles, and the pressures of modern life have all contributed to smaller family sizes. "There has been a significant redefinition of what constitutes a successful life," noted a cultural anthropologist from Yale. "For many, career, education, and personal development have taken precedence over traditional family roles."

A Harris advisor summarized the situation bleakly: “The economic incentives to have children are upside-down. The middle class is shrinking, the rich don’t need large families to sustain their wealth, and the poor simply can’t afford to bring new lives into the world.”

Women's Workforce Participation: Correlation, Not Causation

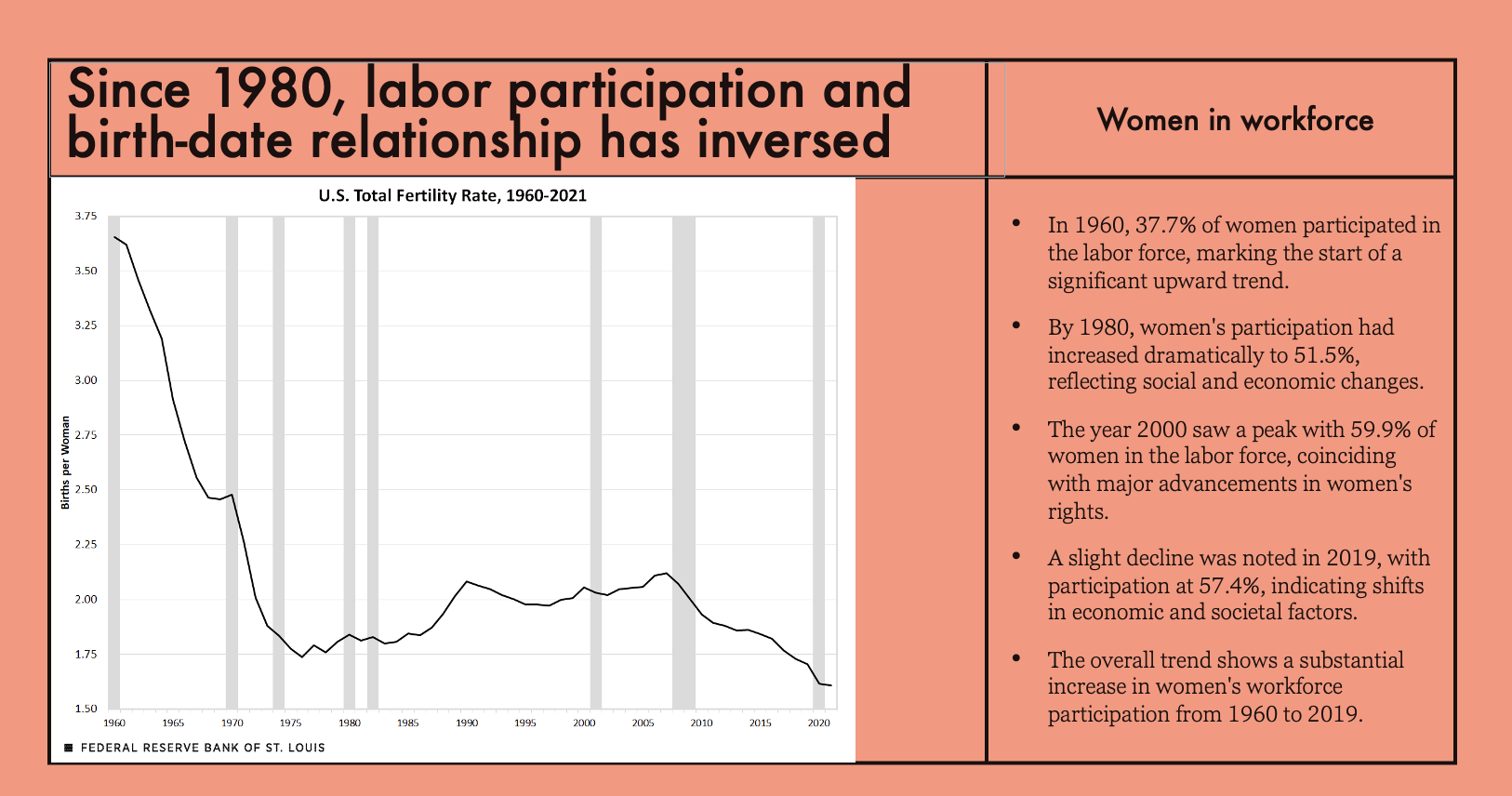

One common explanation for declining birth rates points to the increasing participation of women in the workforce. The narrative seems straightforward—more women working outside the home, fewer children being born. But this view oversimplifies the reality, as correlation does not imply causation.

The rise in female labor force participation began in earnest during the 1960s and accelerated throughout the '70s, climbing from 37% to 50% by the time Ronald Reagan entered the White House in 1980. During this same period, birth rates plunged, falling to less than half of what they were in 1960. Yet, even as women's participation continued to rise, birth-rates briefly went up in 80's and 90's.

In the early 2000s, women’s participation in the workforce reached 60%, the high-water mark. Interestingly, during that time, the total fertility rate (TFR) actually ticked upwards from 1.7 to 2.1. Many expected birth rates to continue falling as more women joined the labor force, but the opposite occurred.

“Many economists are starting to believe we've misunderstood the relationship between workforce participation and family size,” noted a labor economist from Yale. "Yes, women entered the workforce in large numbers, but that doesn’t mean they stopped wanting or having children. Other factors, especially economic ones, are likely more influential."

Another theory suggests that as the U.S. shifted from an industrial economy to a service-based one, women were able to balance work and family more effectively. In the service sector, with flexible hours and different career dynamics, women found new ways to participate in the workforce without sacrificing family goals.

"Just because women went to work doesn’t mean they stopped wanting to be mothers," remarked a sociologist. "The question is whether the economic conditions allow them to do both."The economic realities of 2024 make family planning a purely financial decision for many women. "Having children today isn't just a natural next step, it's an economic conversation," said an economist from Harvard. "Women are weighing the joy of motherhood against the burden it could bring."

Economic Considerations and Low Birth Rates

In today's America, the decision to have children is increasingly shaped by economics. Beyond cultural shifts or personal preferences, the rising cost of child-rearing, coupled with economic instability, has made family expansion a daunting proposition for many.

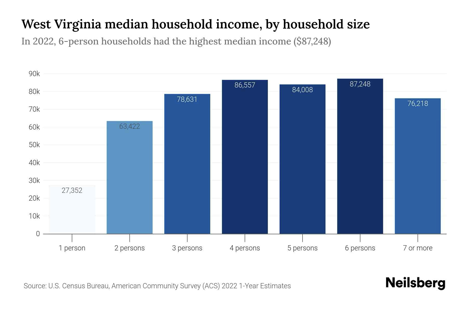

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau reveals the stark financial realities. Married couples in 2020 enjoyed a median household income of $98,700—more than double that of single individuals, who earned a median of $44,000. Dual-income households clearly have an economic advantage, but the equation becomes more complicated with children. As family size increases, the per capita income decreases, making larger families an increasingly difficult financial choice."

Adding a child introduces substantial costs," noted an economist from the University of Chicago. "But for smaller families, the burden can often be mitigated by shared resources and the benefits that come with dependents, such as tax credits."

In a recent study, Neilsberg analyzed family incomes in Arkansas and discovered that larger families early roughly the same as smaller families. Said another way, larger families have less resources to go around per capita, even though the working members work just as much as a smaller family.

This means for larger families the financial strain of having a child is much greater. Households with five or more members see a substantial drop in per capita income, making them more vulnerable to economic instability. "The marginal cost of each additional child beyond the second is enormous," said the same economist. "Beyond the third, it can be prohibitive."

Housing costs are a key factor. The National Association of Realtors reported that the median price of a home in the U.S. reached $310,000 in 2020, a 14% increase from the previous year. More recently, this has ballooned to nearly $400,000, placing homeownership out of reach for many young families.

"Homeownership has traditionally been a key marker of stability, often a precursor to starting a family," remarked a housing policy analyst from Yale. "As housing affordability declines, especially for younger generations, many are delaying both marriage and children."

Unremarkably, renters tend to have fewer children than homeowners. Research from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University found that homeowners, on average, have 0.5 more children than renters of similar age and income levels. “The inability to purchase a home is directly linked to lower birth rates,” added the housing analyst.

Solutions: Policy, Incentives, and the Future of Family Growth

Harris and Trump team both acknowledge the risks from a low birth rate. Yet, both have very different solution proposals. Trump wants to make the family the center of American culture. Harris wants to make the family the center of American economy. In some respects, these differing views suggest the different solutions being proposed by each party.

Children's Social Security

Harris wants to make a woman whole once she has the child. The start will be with a proposed a $6,000-per-year child credit as a step towards making child-rearing less financially burdensome. “We believe that by providing families with a financial safety net, we can encourage family growth without making it feel like an economic gamble,” said a senior Harris advisor.

As we said, though,this is only the start. “Our goal is to develop a social security apparatus for Children. We aim to make having a child a no-regret, no-cost decision for a young mother. This would require paying up to $20k per year per child, essentially making the society as a whole responsible for the child.”

This is the most important part of the plan, which if realized would cost $1.8 trillion a year. The math is simple, a child costs an average American family roughly $300k to raise. If the government takes that burden than the rationale goes many more families would be having children, reversing the declining and aging population and also solving for immigration crisis.

An economist we spoke to supports the idea. “We have a long-running study at Stanford, where we have looked at the cost of bringing a child and its impact on children born. Through the course of our study, we basically stopped seeing many participants having the third child. Without fail, the reason has been economic.”

Trump team dismisses the notion and believes the plan is dangerous and is only going to result in higher taxes and wealth transfer. The Trump camp has proposed a different approach: offering free in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments to address fertility challenges. “We are the party of family values,” noted a Trump advisor. “But family values don’t mean making it easy or cheap. We’re focused on supporting those who genuinely want children but face biological barriers.” This proposal taps into the cultural narrative of restoring family size without turning to what Trump’s team views as socialist policies like tax breaks for all families.

Reducing the Opportunity Cost of Parenthood

Beyond direct financial incentives, both sides are considering policies that reduce the opportunity cost of having children, particularly for women. Universal pre-kindergarten education, paid parental leave, and subsidized childcare are among the options. “For most families, the real cost is not just money—it’s time,” said a Harris advisor. "We want to ensure that parents, particularly women, don't have to choose between their careers and having children."

The Trump team, however, is less keen on broad subsidies. "Paid leave and universal childcare might sound appealing," noted a Trump aide, "but they’re expensive and inefficient. We need to encourage families to rely on themselves and their communities, not the government."

Addressing Housing Affordability

Another area in which the two sides differ is Housing. “Housing affordability is the key reason we have seen the recent decline in birth rates,” pointed an economist at Yale. “Data from the National Association of Realtors shows that homeownership is closely linked to family size, with homeowners typically having more children than renters. To make homeownership more attainable, Harris’s plan includes expanded housing credits, reduced down payment requirements, and increased affordable housing availability.“

We can't ask families to have more children when they can’t even afford a home,” said a housing policy expert advising the Harris campaign. "If we make homeownership possible for more Americans, we indirectly support larger families."

Trump team believes the plan is a thinly veiled way of building houses for illegal aliens. “Look, we know who will be getting the new houses Kamala is proposing,” a Trump aide told us. “What you need is lower taxes, not these new ways of subsidizing a population which isn’t playing by the rules.”

A Cultural Shift in Policy

Both sides also acknowledge the need for a broader cultural shift in how the country views family formation. Harris’s team emphasizes the importance of policies that encourage family growth in a way that’s economically viable, while the Trump team is focused on restoring traditional family values.

As a Harris advisor put it: “It’s about creating a future where having children is a choice, not a burden.” The Trump camp, meanwhile, insists that it’s about restoring self-reliance: “We don’t need to bribe people into having kids,” remarked a Trump advisor. “We need to create a society where family is once again the natural choice.”

The Demographic Tipping Point: A Looming Crisis of Inequality

As the U.S. edges closer to a demographic tipping point, the question of how the country will balance its aging population with a shrinking workforce looms large.

By 2035, the Social Security Administration projects there will be just 2.3 workers for every retiree, down from 3.0 in 2020. The economic consequences of this shift are enormous. With fewer young people entering the workforce, the strain on social welfare programs, already growing, is set to become unsustainable.“We’re headed for a crisis if nothing changes,” warned a senior policy analyst from the Brookings Institution. "Our current system is built on a younger workforce supporting an older population, and that balance is tipping. The math no longer works."

One potential solution lies in boosting birth rates, but as we’ve seen, this is easier said than done. Immigration is often cited as another option to offset a declining workforce, but political resistance and fluctuating immigration policies make this solution tenuous at best.

Both sides agree, more immigration won't solve the problem in the long run.

Economic Fallout

Without a proportional increase in the younger workforce, experts predict that tax hikes or cuts to benefits will be inevitable.

“Either we increase taxes on the younger generation, or we cut benefits to the older one,” noted a Harvard economist specializing in public policy. "Neither option is politically popular, but something has to give."The housing market, already inflated, may become even more unaffordable for younger generations. “If we continue down this path, housing costs will remain out of reach for many Gen Z and future generations,” said a housing policy analyst. "This will have knock-on effects on family formation, further suppressing birth rates."

Additionally, wealth inequality is expected to widen, with wealthier families investing more in their fewer children. A 2021 report from the Department of Education showed that families earning over $100,000 spend nearly twice as much on their children’s education compared to families earning $50,000 or less. The result is a stratified society where upward mobility becomes increasingly difficult. “We’re not just talking about economic capital, but also social capital,” noted a sociologist from the University of California. "The rich are investing heavily in their children’s future, leaving the rest of society behind."

Looking Ahead

As the white population becomes a slimmer majority, their influence at the ballot box may remain outsized. By 2050, whites are projected to comprise about 60% of eligible voters despite being less than 50% of the population. This imbalance is due in part to higher voter registration and turnout rates among white voters."

Demographic shifts don’t necessarily translate into political power," said a political scientist. "If minority populations feel economically marginalized and politically underrepresented, it could lead to increased social tensions and a crisis of legitimacy for democratic institutions."

Hispanic voters, despite being projected to make up 25% of the population by 2050, are expected to account for only about 13% of the voter base. Factors such as lower naturalization rates and younger median ages—meaning many Hispanics will still be too young to vote—are expected to maintain this imbalance.

The demographic and economic pressures America now faces demand swift action. Experts across the political spectrum agree on one thing: the window for meaningful change is closing fast.

A senior economist who helped draft the "Financial Strategies" whitepaper had the final word: "We can either spend the money we have today on the young, or we won't have it to spend on the elderly later—it's not a difficult choice."